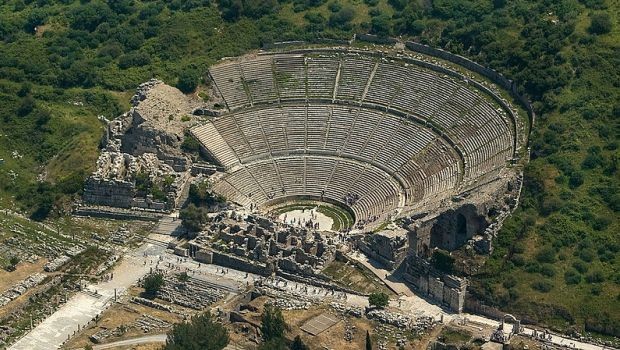

The Grand Theater of Ephesus today, is one of the most impressive and well-preserved ancient structures in Turkey. But this wasn’t always the case. For centuries, this magnificent theater lay hidden beneath layers of earth and debris, its grandeur concealed from the world.

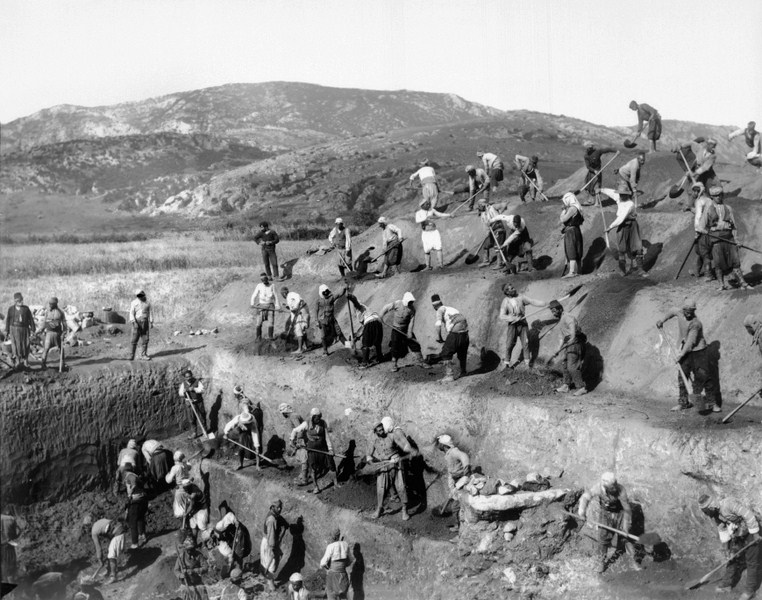

In the 1860s, when British archaeologist John Turtle Wood began excavations at Ephesus, the theater was little more than a large mound of earth on the slope of Panayir Hill. At that time, no one could have imagined the architectural marvel that lay beneath. The initial excavations revealed tantalizing glimpses of the structure, but it wasn’t until the Austrian Archaeological Institute took over the site in 1895 that systematic excavation and restoration work began in earnest.

The task facing the archaeologists was daunting. Centuries of neglect, earthquakes, and the gradual accumulation of sediment had buried the theater under layers of debris. The upper sections of the cavea (seating area) had collapsed, and much of the structure was hidden from view.

As excavations progressed, the true scale and beauty of the theater began to emerge. The semi-circular orchestra pit, a hallmark of Roman design, was uncovered. The massive seating area, capable of holding up to 25,000 spectators, was gradually revealed. The ornate stage building, with its elaborate columns and statues, began to take shape.

The excavations also shed light on the theater’s long history. Evidence of its Hellenistic origins in the 3rd century BC was uncovered, as well as signs of later Roman expansions and renovations. The discovery of inscriptions and architectural elements allowed archaeologists to piece together the theater’s evolution over time.

In the 1970s and 1990s, extensive restoration work was carried out on the cavea. This involved not just clearing away debris, but carefully reconstructing collapsed sections using original materials where possible. The goal was to preserve the theater’s authenticity while making it safe for modern visitors.

From a nondescript mound of earth, it has been transformed back into the awe-inspiring structure it once was. Visitors can now walk through the same corridors and sit on the same stone seats as ancient Greeks and Romans did over two millennia ago.