The Rock Art of the Wandjina Sky Beings presents a fascinating glimpse into the ancient spiritual beliefs and artistic traditions of Aboriginal Australians

These enigmatic figures, found primarily in the Kimberley region of northwestern Australia, have captivated researchers and art enthusiasts for decades with their distinctive appearance and profound cultural significance.

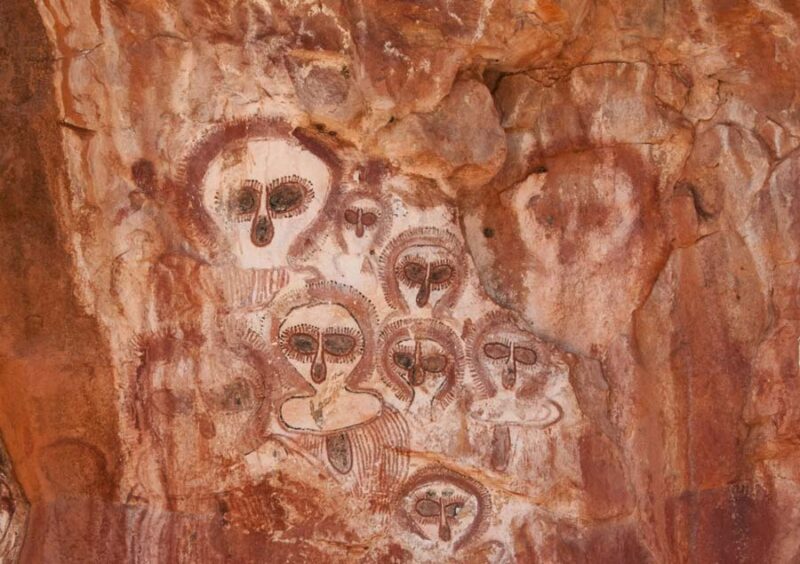

The Wandjina are depicted as large, ethereal beings with striking features: round owl-like faces, large black eyes, and elaborate halos or headdresses surrounding their heads. Curiously, they lack mouths. Painted in vibrant white, red, and yellow ochres on rock shelter walls and ceilings, these figures have endured for at least 4,000 years, though some researchers suggest they may be even older.

For the Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Wunambal peoples, the Wandjina are not mere artistic expressions but powerful creator beings from the Dreamtime. According to their traditions, these sky spirits descended from the Milky Way during the creation period to shape the land and establish laws for the people. The Wandjina are intimately connected to the cycles of nature, particularly the monsoon rains that bring life-giving water to the arid landscape.

What makes the Wandjina rock art truly remarkable is its continuity as a living tradition. Unlike many ancient rock art sites around the world that have been abandoned or forgotten, Wandjina sites are still actively maintained and repainted by Aboriginal artists today. This practice, which has endured for millennia, speaks to the enduring cultural and spiritual significance of the Wandjina to the peoples of the Kimberley.

The unique stylized appearance of the Wandjina has led to much speculation about their origins and meaning, particularly among non-Indigenous observers. Some researchers have drawn parallels to alien or astronaut figures, though Aboriginal elders firmly reject such interpretations as misunderstandings of their cultural heritage.

Interestingly, while the Wandjina are unique to the Kimberley region, there are some intriguing parallels with rock art traditions in other parts of the world. For example, the large eyes and lack of mouths on Wandjina figures bear a striking resemblance to certain petroglyphs found in the American Southwest, particularly in Utah’s Nine Mile Canyon. These “Fremont style” anthropomorphs, created by ancient Native American cultures, often feature large, staring eyes and simplified facial features.

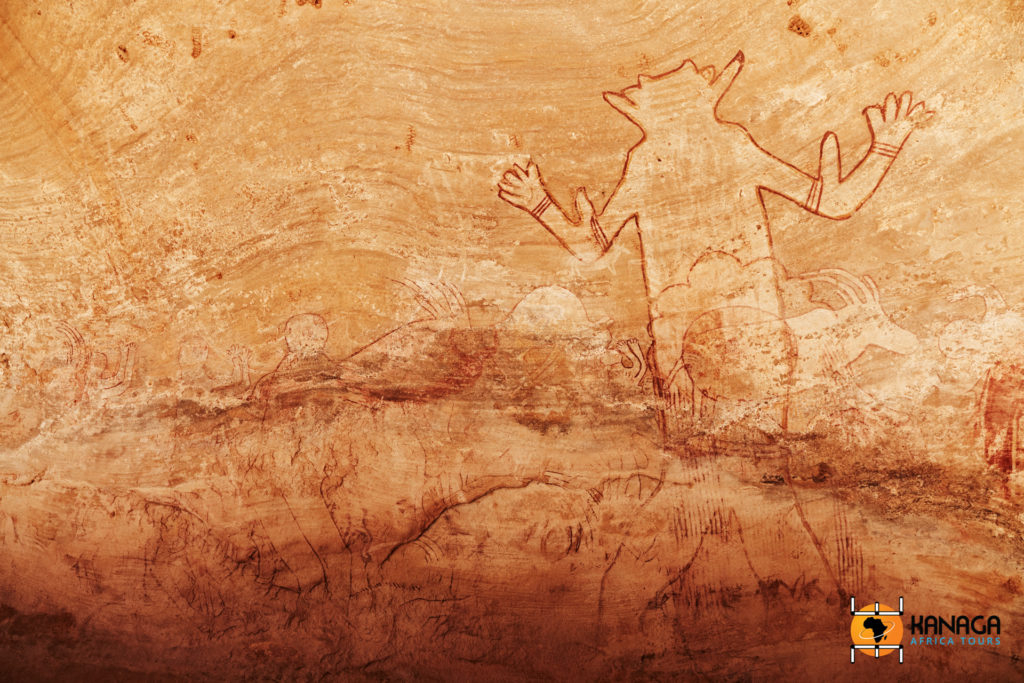

Another fascinating connection can be drawn to the “Tassili n’Ajjer” rock art in Algeria, where some figures are depicted with round, featureless faces and elaborate headdresses, reminiscent of the Wandjina’s distinctive appearance. While these similarities are likely coincidental, they highlight the universal human impulse to create powerful, otherworldly figures in rock art across cultures and continents.

The Wandjina tradition also shares common themes with other indigenous art forms around the world, particularly in its connection to creation stories and the natural environment. Like the Wandjina, many Native American rock art sites depict spirit beings and creation narratives. Similarly, San rock art in southern Africa often portrays trance visions and spiritual transformations, echoing the Wandjina’s role as powerful, transformative beings.

One of the most striking aspects of Wandjina art is its association with weather and natural cycles. The Wandjina are believed to control the monsoon rains, and their repainting is often tied to seasonal rituals. This connection between rock art and weather phenomena is not unique to Australia. In the Andes, for instance, ancient Peruvian cultures created geoglyphs and rock art that were likely tied to water and fertility rituals in the arid coastal regions.

The conservation of Wandjina sites presents both challenges and opportunities. Like many rock art traditions worldwide, Wandjina paintings face threats from weathering, vandalism, and development. However, the living nature of the Wandjina tradition offers a unique model for rock art conservation. By involving Indigenous communities in the protection and management of these sites, authorities have been able to preserve not just the physical artwork but the cultural knowledge and practices associated with it.

This approach resonates with emerging best practices in rock art conservation around the world. From the Serra da Capivara National Park in Brazil to the Côa Valley in Portugal, there is growing recognition of the importance of involving local communities and indigenous knowledge holders in the stewardship of rock art sites.

The Wandjina rock art tradition, with its striking imagery and living cultural significance, offers a powerful reminder of the depth and continuity of indigenous Australian culture.