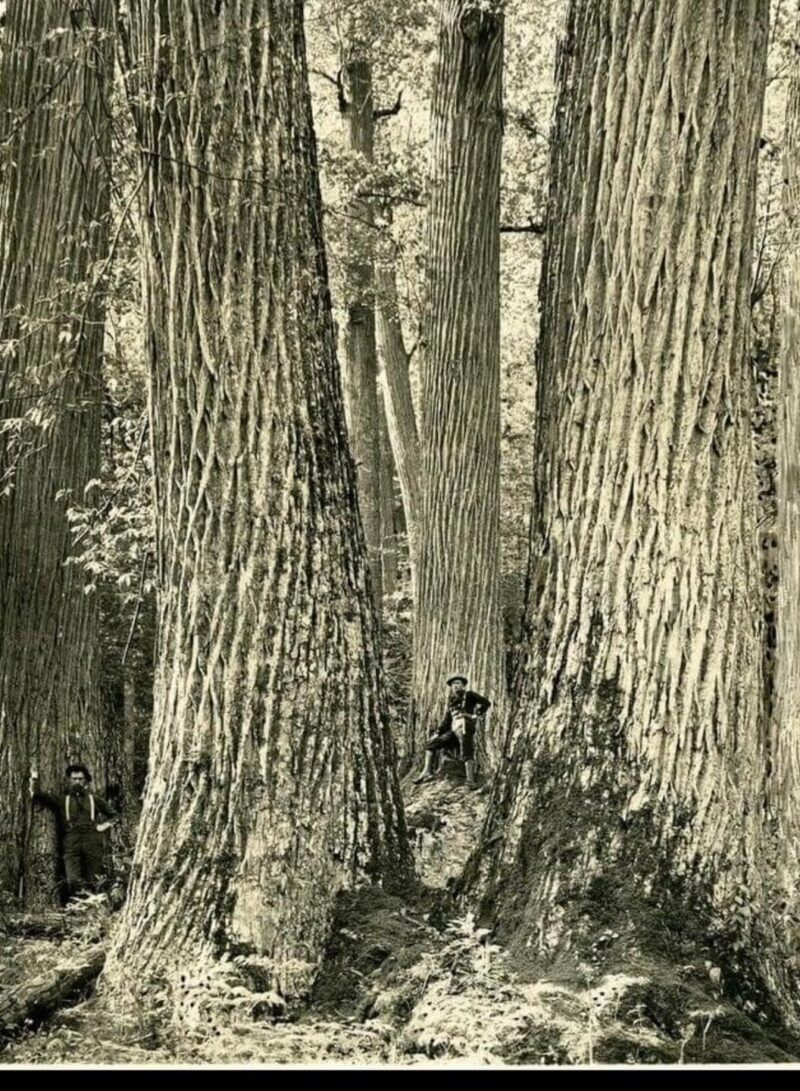

The American chestnut tree (Castanea dentata) once stood as a colossus in the Appalachian forests, its towering presence overlooking natural abundance and biodiversity.

Known affectionately as the “redwood of the East,” these magnificent trees dominated the landscape from Maine to Mississippi, their sprawling canopies stretching over 100 feet into the sky. The chestnut’s reign in these mountains was not just a matter of size and number; it was an integral part of the ecosystem, the economy, and the very fabric of Appalachian culture.

In its heyday, the American chestnut comprised a staggering one-quarter of all trees in eastern U.S. forests, with an estimated population of four billion. These trees were not merely plentiful; they were prolific producers of nuts, with a single mature tree capable of yielding up to 6,000 chestnuts annually. This abundance of nuts provided a crucial food source for a wide array of wildlife, from white-tailed deer and wild turkeys to the now-extinct passenger pigeon. The chestnut’s nutritional bounty extended beyond the forest, becoming a staple in the diets of Appalachian communities and their livestock.

The versatility of the American chestnut was unparalleled. Its straight-grained, rot-resistant wood was prized for construction, from humble fence posts to grand furniture pieces. The tree earned the moniker “cradle to grave tree,” as its wood accompanied mountain folk throughout their lives, from the cradles of their infancy to the coffins of their final rest. This versatility made the chestnut an economic powerhouse for the region, providing a reliable source of income for rural families who harvested and sold the nuts and timber.

However, the reign of the American chestnut came to an abrupt and tragic end with the introduction of a microscopic invader. In 1904, a fungal blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) was accidentally introduced to North America through imported Asian chestnut trees. This seemingly innocuous event set in motion what has been described as

“the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world’s forests in all of history”.

The blight spread with alarming speed, moving at an average rate of 25 miles per year. It was merciless in its efficiency, attacking the trees through wounds in their bark and effectively girdling them, cutting off the flow of nutrients. Within 40 years of its introduction, the blight had ravaged the chestnut population, reducing the once-dominant species to functional extinction.

The loss of the American chestnut reverberated through the Appalachian ecosystem and economy. The sudden absence of this keystone species left a void that other trees, particularly oaks, rushed to fill. This shift in forest composition had cascading effects on wildlife populations and soil composition, altering the very nature of the Appalachian forests.

For the people of Appalachia, the loss was deeply personal and economically devastating. Families who had relied on chestnut harvests to supplement their incomes suddenly found themselves without this crucial resource. The timing couldn’t have been worse, coinciding with the onset of the Great Depression. The chestnut’s demise marked not just the loss of a tree, but the erosion of a way of life that had sustained mountain communities for generations.

Despite this ecological catastrophe, the American chestnut has shown remarkable resilience. While mature trees are now exceedingly rare, the species persists in the form of stump sprouts that emerge from the roots of fallen giants. These sprouts, though typically short-lived due to the persistent blight, serve as a living reminder of the chestnut’s former glory and its refusal to fade entirely from the Appalachian landscape.

This tenacity has inspired a dedicated effort to restore the American chestnut to its former prominence. Organizations like The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) have been at the forefront of this restoration effort, employing advanced breeding techniques to develop blight-resistant trees. One promising approach involves the Darling 58 tree, which retains 100% of its American chestnut genes with the addition of a single gene from wheat that confers blight resistance.

The potential return of the American chestnut to Appalachia holds promise not just for ecological restoration, but for economic revitalization as well. As Susan Thompson, a graduate student working on chestnut restoration, notes, “If you are thinking about how I can make a living off of trees, in farming, the chestnut is a species that you’re going to want to plant because they’re very marketable”. The chestnut’s potential as a sustainable crop could provide new opportunities for Appalachian farmers and forest managers.

The restoration of the American chestnut could play a crucial role in enhancing the resilience of Appalachian forests in the face of climate change. The Appalachian Mountains, with their varied elevations and microclimates, are a refuge for many species adapting to changing conditions. The reintroduction of the chestnut could further enhance this biodiversity, providing additional food and habitat options for wildlife.

The story of the American chestnut in Appalachia is one of profound loss, but also of hope and resilience. It’s a poignant reminder of the delicate balance of ecosystems and the far-reaching consequences of human actions on the natural world. At the same time, it demonstrates the power of human ingenuity and determination in the face of ecological challenges.

As efforts to restore the American chestnut continue, the tree has become a symbol of the Appalachian spirit itself. As Thompson eloquently puts it, “The story of the American chestnut is the story of the Appalachian people — downtrodden, impacted in ways that just really cut it down, but coming back anyway”. This sentiment encapsulates the connection between the people of Appalachia and their natural environment, a relationship that has weathered significant challenges but continues to evolve and persevere.

The potential return of the American chestnut to the forests of Appalachia symbolizes the restoration of a vital piece of the region’s ecological and cultural heritage. As blight-resistant chestnuts are planted and nurtured, they carry with them the hopes of scientists, conservationists, and local communities alike.

As hikers traverse the Appalachian Trail today, they may occasionally stumble upon the remnants of the chestnut’s former dominance – a decaying stump here, a struggling sprout there. These encounters serve as poignant reminders of the forest’s history and the ongoing efforts to shape its future. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy, recognizing the significance of these trees, has even enlisted the help of hikers in identifying surviving chestnuts along the trail.

The story of the American chestnut in Appalachia is far from over. As research progresses and restoration efforts continue, there is hope that future generations may once again witness the grandeur of chestnut-covered hillsides. The return of this iconic species could herald a new era of ecological balance and economic opportunity in the region, breathing new life into the forests and communities of Appalachia.