The colossal stone statues of Rapa Nui, known to much of the world as Easter Island, have captivated the imagination of explorers, researchers, and dreamers for centuries. These monolithic human figures, called moai, stand silent along the island’s coast, their enigmatic expressions gazing inland as if watching over the land and its people. The moai represent one of the most impressive achievements of Polynesian culture and continue to be a source of wonder, debate, and ongoing research.

Origins and Age of the Moai

Traditional archaeological dating places the construction of the moai between 1250 and 1500 CE. This timeline aligns with the estimated arrival of Polynesian settlers on Rapa Nui, thought to have occurred around 1200 CE. However, recent genetic studies and archaeological findings are challenging this conventional chronology, suggesting a more complex history of the island and its iconic statues.

A 2023 study published in Nature analyzed the genomes of 15 ancient Rapanui individuals dated between 1670 and 1950 CE. The research found no evidence of a population collapse in the 1600s, contradicting the popular “ecocide” theory that proposed a dramatic decline due to resource overexploitation. Instead, the genetic data indicated a stable, growing population from the 13th century through to European contact in the 18th century.

This genetic evidence, combined with new archaeological discoveries, has led some researchers to propose that the moai tradition may have deeper roots than previously thought. Some speculate that the earliest settlers might have brought the concept of monumental statuary with them, possibly explaining the sophisticated nature of even the earliest moai.

Oral traditions among the Rapanui people sometimes suggest an even more ancient origin for the moai. Some stories speak of the statues being present when the first settlers arrived, attributing their creation to spiritual or otherworldly forces. While these accounts are not considered historical fact by mainstream archaeology, they highlight the deep cultural significance of the moai and the complex relationship between the Rapanui people and their monumental heritage.

The Polygonal Wall: Pushing Back Rapa Nui’s Timeline

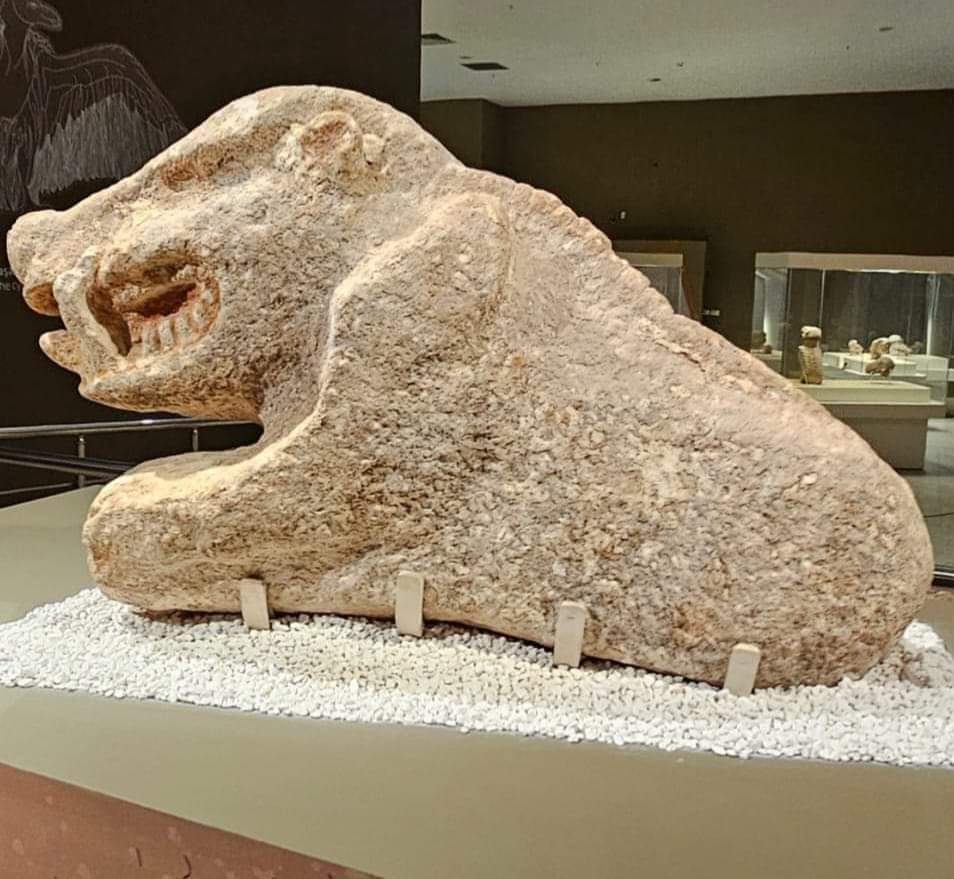

While the moai statues of Rapa Nui have long captivated the world’s attention, a lesser-known but equally intriguing feature of the island’s ancient architecture is its polygonal stonework. This sophisticated masonry technique, found in structures like the Ahu Vinapu, has led some researchers to question the conventional timeline of Rapa Nui’s settlement and cultural development.

The polygonal wall at Ahu Vinapu bears a striking resemblance to Incan stonework found in Peru, particularly at sites like Ollantaytambo and Machu Picchu. The precision with which these large, irregularly shaped stones are fitted together without mortar is remarkable, with joints so tight that even a razor blade cannot be inserted between them. This level of craftsmanship is typically associated with much older and more technologically advanced civilizations.

Some researchers argue that the presence of this advanced stonework technique on Rapa Nui suggests a much earlier date for the island’s settlement or, at the very least, indicates contact with South American cultures long before European arrival. This theory is supported by other lines of evidence:

- Genetic studies: Recent genetic research has revealed that the Rapanui people have a small but significant amount of Native American DNA, estimated to have been introduced between 1250 and 1430 CE.

- Sweet potato cultivation: The presence of sweet potatoes, a crop native to South America, in ancient Polynesian sites has long suggested pre-Columbian contact between Polynesia and the Americas.

- Linguistic similarities: Some researchers have pointed out linguistic parallels between Rapa Nui and certain South American languages, though this remains a topic of debate.

Bananas have played a significant role in Rapa Nui’s agricultural history, with some researchers suggesting they may provide evidence for an earlier settlement date of the island. Dr. Jean-Yves Empereur, an archaeologist who has studied the island’s plant remains, has proposed that certain banana varieties found on Rapa Nui could be traced back to much earlier periods than previously thought. His research indicates that some banana cultivars might have been introduced to the island as early as 300-400 CE, significantly predating the conventional timeline of Polynesian settlement around 1200 CE. This theory is based on genetic analysis of banana varieties unique to Rapa Nui and comparisons with other Polynesian and South American banana types. While this research remains controversial and is not universally accepted by the archaeological community, it highlights the potential of plant genetics and archaeobotany to provide new insights into the island’s settlement history and challenge established timelines.

The polygonal wall at Ahu Vinapu, suggests that the wall could be evidence of a much older, perhaps global, advanced civilization that predates current estimates of Polynesian expansion into the Pacific.

The debate surrounding the polygonal wall highlights the ongoing challenge of accurately dating and interpreting the archaeological record of Rapa Nui. As new technologies and methodologies emerge, researchers continue to refine their understanding of the island’s chronology.

The Moving Mystery

One of the most enduring mysteries surrounding the moai is how they were transported from the quarry at Rano Raraku to their final positions around the island. Various theories have been proposed over the years, from the use of log rollers to extraterrestrial intervention. However, recent research has lent credence to a method that aligns with Rapanui oral traditions: the moai were “walked” to their destinations.

Terry Hunt of the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Carl Lipo of California State University Long Beach, working with Rapanui archaeologist Sergio Rapu, have demonstrated the feasibility of this method. Their theory proposes that teams of workers used ropes to rock the moai back and forth, creating a walking motion while keeping the statue upright. This technique would explain the presence of fallen moai along ancient roads, as they could have toppled during transport and been too heavy to right again.

The walking theory is supported by the physical characteristics of the moai themselves. Many have a forward lean and a rounded base, features that would facilitate the rocking motion necessary for “walking.” Additionally, this method would require fewer people and resources than alternative theories involving sleds or rollers, aligning with estimates of the island’s historical population.

The Depth of Burial: An Anomaly in Time

One of the most intriguing aspects of the moai is the depth at which many are buried. Some statues are interred up to their shoulders, with only their iconic heads visible above ground. This extensive burial has puzzled researchers, as it seems excessive for statues believed to be only 500-800 years old.

Several explanations have been proposed for this phenomenon:

- Intentional burial: Some researchers suggest that the moai were deliberately buried to this depth for stability or ritual purposes.

- Gradual accumulation: Over centuries, wind-blown sediment and organic matter could have accumulated around the bases of the statues.

- Volcanic activity: Rapa Nui has a history of volcanic eruptions, which could have deposited ash and other materials around the moai.

- Ancient origin theory: The depth of burial indicates a much greater age for the moai than conventionally accepted, suggesting they could be thousands of years old.

While the conventional explanation favors a combination of intentional placement and natural accumulation, the depth of burial remains a point of discussion among researchers and enthusiasts alike.

Global Echoes: The Hands Clasped Around the Belly

One of the most striking features of many moai is the position of their hands, clasped around their belly. This pose is not unique to Rapa Nui; similar depictions can be found in monumental statuary around the world, from the Olmec colossal heads in Mexico to certain Egyptian statues. The global occurrence of this particular posture has intrigued researchers and enthusiasts alike, leading to various interpretations and theories about its significance and origin.

Some archaeologists and anthropologists suggest that this similarity across cultures could be an example of convergent evolution. In this view, different societies may have independently developed this pose to represent concepts such as authority, wisdom, or contemplation. The universality of human body language and gestures could explain why diverse cultures arrived at similar artistic expressions.

Another interpretation proposes that these similarities indicate ancient cultural connections or even a common origin for these seemingly disparate civilizations. Proponents of this theory argue that the specific hand position, combined with other shared artistic and architectural elements, could be evidence of long-forgotten global exchanges or migrations.

From a symbolic perspective, the hand position clasped around the belly might represent a universal human gesture related to introspection, power, or spiritual practices. Some researchers speculate that this pose could have held similar meanings across cultures, perhaps relating to concepts of fertility, abundance, or inner knowledge.

Practical considerations also play a role in these discussions. The pose, with hands clasped around the belly, provides a stable and balanced form for stone carving. This practical aspect could explain its prevalence in monumental statuary across different cultures, as it allows for the creation of durable and visually striking figures.

While mainstream archaeology generally favors explanations based on convergent evolution or common human symbolism, the global occurrence of this pose continues to fuel discussions about potential ancient cultural exchanges. As research methods advance and new discoveries are made, our understanding of these intriguing similarities may evolve, potentially shedding new light on the connections between ancient cultures across vast distances.

The Intricate Carvings of the Moai: A Global Perspective

The moai of Rapa Nui are also for the intricate carvings that adorn their bodies. These carvings, often overlooked in favor of the statues’ more prominent features, provide valuable insights into the artistic traditions and symbolic language of the ancient Rapanui culture. Interestingly, some of these carvings bear striking similarities to those found on statues at other ancient sites around the world, including Göbekli Tepe in Turkey.

On many moai, complex designs and symbols are etched into the back and sometimes the front of the statues. These carvings include geometric patterns, stylized human figures, and various symbols whose meanings remain the subject of ongoing research and debate. Some of the most common motifs include:

- Birdman figures: Representations of the tangata manu, a central figure in Rapanui mythology and ritual.

- Komari: Vulva-shaped designs that may represent fertility or lineage.

- Ao (ceremonial paddles): Symbols of authority and leadership.

- Spiral patterns: Possibly representing waves or other natural phenomena.

The presence of these intricate carvings suggests that the moai were not merely representations of ancestors or deities but also served as complex symbolic texts, conveying information about Rapanui culture, history, and cosmology.

Intriguingly, some of the carved motifs on the moai share similarities with those found on ancient statues and structures at other sites around the world. For example, the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe, dating back to around 10,000 BCE, also feature intricate carvings of animals, human figures, and abstract symbols. While the specific motifs differ, the practice of adorning monumental stone structures with detailed symbolic carvings appears to be a shared feature across these cultures separated by vast distances and time.

At Göbekli Tepe, recent excavations have uncovered even more statues with complex carvings. In 2023, archaeologists discovered a painted wild boar statue decorated with red, white, and black pigments, as well as a 2.3-meter-tall human statue with realistic facial features. These finds, along with previously discovered animal reliefs depicting snakes, insects, birds, and other creatures, echo the diverse range of subjects carved onto the moai of Rapa Nui.

The similarities in carving practices between Rapa Nui and sites like Göbekli Tepe raise questions about the development of monumental sculpture and symbolic representation in ancient cultures.

Some researchers propose that these similarities could indicate a shared ancestral tradition of symbolic representation that spread across ancient cultures. Others suggest that they represent convergent evolution in artistic and symbolic practices, with different cultures independently developing similar approaches to imbuing their monumental structures with meaning.

The study of these carvings continues to be a rich area of research, with new technologies like 3D scanning and photogrammetry allowing for more detailed analysis and comparison of motifs across different sites.

Color and Life: The Eyes of the Moai

According to Rapanui oral tradition, the moai only truly came to life when their eyes were completed. This belief is supported by archaeological evidence discovered in 1979 by Sergio Rapu Haoa and his team. They found that the eye sockets of the moai were designed to hold coral eyes with pupils made of either black obsidian or red scoria.

The addition of eyes would have dramatically changed the appearance of the moai, transforming them from stark stone figures to more lifelike representations. This final touch may have been part of a ritual process, symbolizing the awakening of the ancestor spirit represented by the statue.

Evidence suggests that not all moai received eyes, indicating a possible hierarchy among the statues. Those with carved eye sockets were likely allocated to the most important ahu (stone platforms) and ceremonial sites, reflecting their elevated status in Rapanui cosmology.

The use of color was not limited to the eyes. Traces of pigments found on some moai suggest that they may have been painted, possibly in vibrant colors that would have made them even more striking against the island’s landscape.

European Contact and Cultural Devastation

The arrival of European explorers in the 18th century marked the beginning of a tragic period for Rapa Nui and its moai. The Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen first encountered the island on Easter Sunday, 1722, giving rise to its Western name. Subsequent visits by Spanish, British, and French expeditions brought disease, violence, and cultural disruption.

The most devastating blow came in the 1860s when Peruvian slave raiders abducted a significant portion of the island’s population, including many of the ruling class and those with knowledge of the moai traditions. Those who survived and returned brought diseases that further decimated the population.

By the time of annexation by Chile in 1888, the Rapanui population had been reduced to just 111 individuals. This demographic collapse led to a significant loss of cultural knowledge, including many of the oral traditions surrounding the moai.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, numerous moai were removed from the island by foreign expeditions. Some ended up in museums around the world, while others were lost at sea during transport. This pillaging not only physically removed important cultural artifacts but also contributed to the erosion of Rapanui cultural practices and knowledge.

Connections to Other Megalithic Sites

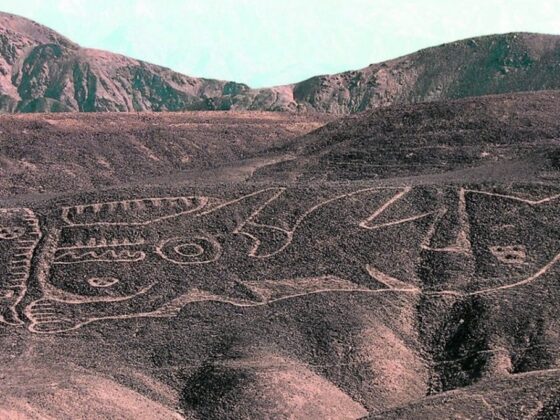

The moai of Rapa Nui share intriguing similarities with megalithic sites around the world, leading some researchers to propose connections between these ancient cultures. These parallels continue to fuel discussions about potential ancient global connections and the capabilities of early civilizations.

One of the most striking similarities is the precision stonework found in some ahu platforms on Rapa Nui. The fine joinery and tight-fitting stones echo the remarkable masonry techniques found in Incan sites like Machu Picchu or the megalithic structures of Malta. This level of craftsmanship, achieved without mortar and using massive stone blocks, has led some researchers to speculate about shared building techniques or knowledge transfer between these geographically distant cultures.

Astronomical alignments present another intriguing parallel. Some ahu on Rapa Nui are oriented to specific celestial events, a feature shared with many other ancient sites worldwide. This characteristic is reminiscent of the famous alignments at Stonehenge in England or the precise astronomical orientations found at Chichen Itza in Mexico. The incorporation of celestial observations into monumental architecture suggests a sophisticated understanding of astronomy across these ancient cultures, raising questions about the development and spread of this knowledge.

The transportation and erection of massive stones is another area of similarity that has captured researchers’ attention. The techniques used to move the multi-ton moai across Rapa Nui may have parallels with methods employed at other megalithic sites. For instance, the transportation of enormous stone blocks at Baalbek in Lebanon or the movement of the colossal Olmec heads in Mexico present similar engineering challenges. These parallels have led to speculation about shared technologies or problem-solving approaches among ancient cultures.

From a cultural perspective, the moai, like many megalithic structures worldwide, appear to have served important ritualistic and possibly astronomical functions within their society. This cultural significance, often tied to ancestor worship or the veneration of elite individuals, is a common thread among many ancient monumental sites. The investment of substantial resources and labor into these projects suggests similar social structures and belief systems may have been at play across different cultures.

The parallels continue to intrigue researchers and fuel theories. Some propose that these similarities could indicate ancient global connections, possibly through maritime trade routes or shared ancestral knowledge. Others suggest the possibility of a more advanced “mother culture” that influenced various ancient civilizations.

Regardless of the interpretation, the similarities between Rapa Nui’s moai and other megalithic sites worldwide continue to fascinate both researchers and the public. .

Recent Discoveries and Ongoing Research

Archaeological work on Rapa Nui continues to yield new insights into the moai and the culture that created them:

- Underground moai: In 2022, a previously unknown moai was discovered buried in a dry lake bed in the Rano Raraku volcano crater. This find suggests that there may be more undiscovered statues on the island.

- Soil fertilization: Recent studies have shown that the areas around the moai have higher levels of nutrients, suggesting that the statues may have played a role in agricultural practices, possibly through ritual offerings that enriched the soil.

- 3D mapping: Advanced technologies like LiDAR and photogrammetry are being used to create detailed 3D maps of the moai and ahu, revealing previously unnoticed details and aiding in conservation efforts.

- Genetic studies: Ongoing genetic research on both ancient and modern Rapanui populations is providing new insights into the island’s settlement history and population dynamics.

- Climate change impacts: Researchers are studying the effects of rising sea levels and increased storm activity on the coastal ahu and moai, developing conservation strategies to protect these irreplaceable monuments.

While archaeological and genetic research have shed new light on their origins and the history of the island, many questions remain unanswered. The depth of their burial, the global echoes in their design, and the sophisticated engineering required for their creation and transport continue to challenge our understanding of ancient capabilities.

Perhaps most importantly, the moai represent the enduring spirit of the Rapanui people. Despite centuries of hardship, including near-extinction following European contact, the Rapanui culture has survived. Today, efforts are underway to revitalize traditional knowledge and practices, including the restoration of moai and ahu across the island.