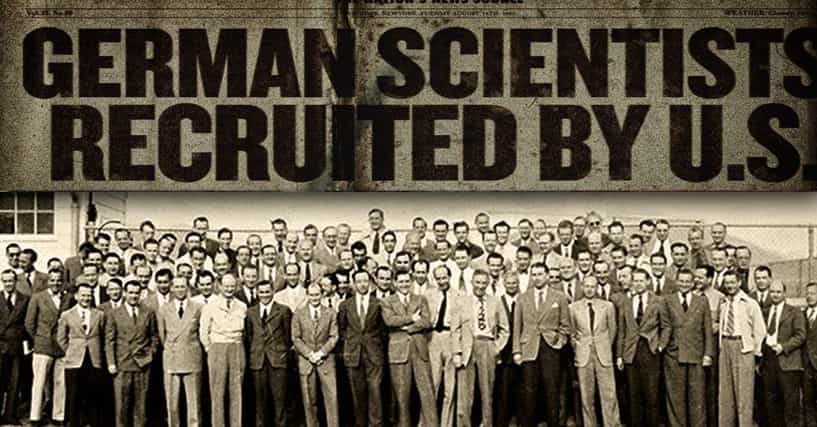

In the aftermath of World War II, as the United States and Soviet Union scrambled to secure the spoils of Nazi Germany’s technological advancements, a clandestine operation known as Operation Paperclip emerged. This controversial program, which lasted from 1945 to 1959, saw the U.S. government recruiting an estimated 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians – many of whom had been members of the Nazi Party and some even implicated in war crimes.

Origins and Motivations

The roots of Operation Paperclip can be traced to the final months of World War II. As Allied forces advanced into German territory, they discovered the extent of Nazi scientific achievements, particularly in rocketry, aviation, and chemical warfare. The U.S. government, recognizing the potential military and scientific value of this knowledge, initiated efforts to secure these technologies and the minds behind them.

The program’s name allegedly came from the paperclips used to attach new identities to the files of scientists whose Nazi backgrounds might otherwise have excluded them from entering the United States. This detail underscores the controversial nature of the operation from its inception.

Key Figures and Recruitment

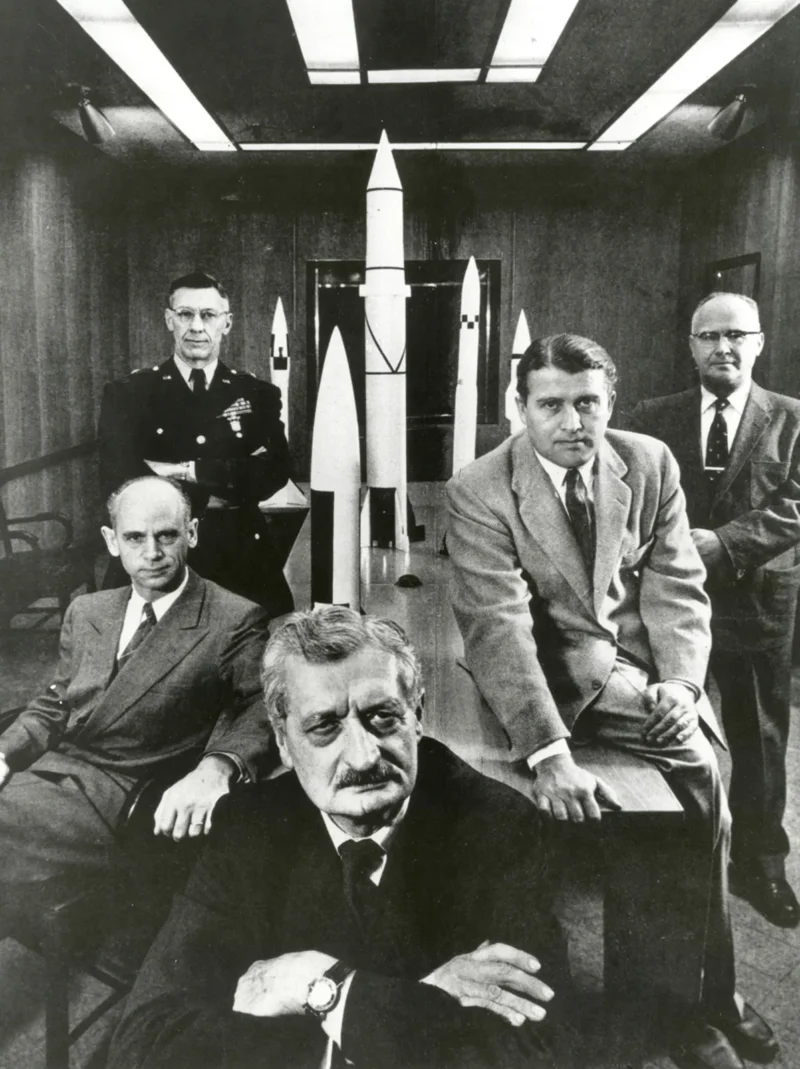

One of the most famous scientists brought to the U.S. through Operation Paperclip was Wernher von Braun, the chief architect of the Nazi V-2 rocket program. Von Braun would go on to become a key figure in the American space program, playing a crucial role in the development of the Saturn V rocket that took astronauts to the moon.

Other notable recruits included:

- Arthur Rudolph, who later became project director of the Saturn V rocket program

- Hubertus Strughold, who would be known as “the father of space medicine”

- Kurt Debus, who became the first director of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

The recruitment process was often hasty and fraught with ethical compromises. Many of the scientists had been members of the Nazi Party or the SS, and some had even participated in human experiments in concentration camps. U.S. officials, driven by the perceived urgency of the emerging Cold War, often overlooked or deliberately concealed these troubling backgrounds.

Ethical Concerns and Controversies

The ethical implications of Operation Paperclip were apparent from the start, raising profound moral dilemmas that would haunt the program throughout its existence and long after. At its core, the initiative represented a stark contradiction between stated American values and pragmatic Cold War objectives.

Some of the most controversial aspects included:

- Whitewashing of Nazi pasts: Many scientists’ records were sanitized to facilitate their entry into the U.S.

- Immunity from prosecution: Some recruits effectively escaped accountability for their actions during the war.

- Conflict with denazification efforts: The program undermined broader attempts to remove Nazi influence from postwar German society.

On one hand, the United States had positioned itself as a champion of justice and democracy in the aftermath of World War II. The Nuremberg trials, which began in November 1945, sought to hold Nazi war criminals accountable for their atrocities. Simultaneously, the U.S. was actively pursuing a policy of denazification in its occupied zone of Germany, aiming to purge Nazi influence from German society, culture, and institutions. These efforts were presented to the world as a moral imperative – a necessary step in rehabilitating Germany and preventing the resurgence of fascism.

Yet Operation Paperclip stood in direct opposition to these publicly stated goals. By recruiting scientists and technicians who had worked for the Nazi regime – some of whom were directly implicated in war crimes – the U.S. government was essentially saying that certain forms of expertise were more valuable than the pursuit of justice. This contradiction was not lost on many observers, both within the government and among the general public. Critics argued that by embracing these scientists, America was tacitly condoning their past actions and betraying the very principles it had fought to defend during the war.

The moral quandary deepened when considering the nature of the scientific knowledge being prioritized. Much of the expertise sought through Operation Paperclip was directly related to weapons development – rockets, chemical weapons, and other military technologies. This raised uncomfortable questions about the ethics of using knowledge gained through unethical means. Many of the German scientists had conducted experiments using slave labor from concentration camps or had developed weapons used against civilian populations. By utilizing their expertise, was the U.S. indirectly benefiting from and legitimizing these atrocities?

Furthermore, the program’s secretive nature and the efforts to conceal or downplay the Nazi affiliations of recruited scientists added another layer of ethical concern. This deception not only misled the American public but also potentially violated U.S. immigration laws, which explicitly barred entry to individuals who had been members of the Nazi party. The willingness to bend or break these rules for the sake of scientific advancement suggested a troubling flexibility in the application of law and ethics when national security interests were at stake.

The ethical implications extended beyond the immediate postwar period. By allowing these scientists to evade justice and build new lives and careers in the United States, Operation Paperclip effectively denied closure and accountability to the victims of Nazi crimes. It also sent a message about the relative value placed on different lives and experiences – the suffering of Holocaust victims and other targets of Nazi aggression was, in essence, being weighed against the potential scientific and military benefits these scientists could provide.

In the broader context of the emerging Cold War, Operation Paperclip highlighted the moral compromises nations might make in the name of national security and technological superiority. It set a precedent for prioritizing perceived strategic advantages over ethical considerations, a pattern that would be repeated in various forms throughout the Cold War era and beyond.

Ultimately, the ethical questions raised by Operation Paperclip continue to resonate today. They challenge us to consider the long-term consequences of short-term strategic decisions and the price of progress when it comes at the expense of moral clarity.

Impact on U.S. Scientific and Military Advancements

Despite the ethical concerns, Project Paperclip undeniably contributed to significant advancements in U.S. science and technology. The recruited scientists played crucial roles in various fields, leaving an indelible mark on American scientific and technological progress in the post-war era:

- Space Exploration: German rocket scientists were instrumental in the development of the U.S. space program, culminating in the Apollo moon landings.

- Aviation: Advancements in supersonic flight and aircraft design benefited from German expertise.

- Chemical Warfare: Knowledge of nerve agents like sarin gas informed U.S. chemical weapons programs.

- Medical Research: Some recruits contributed to advancements in aerospace medicine and other fields.

In the fields of rocketry and space exploration, the contributions were perhaps the most visible and far-reaching. Wernher von Braun, the most famous of the Paperclip scientists, became a key figure in the U.S. space program. His expertise in rocket technology, honed during his work on the V-2 rocket for Nazi Germany, proved invaluable to NASA. Von Braun was instrumental in developing the Saturn V rocket, which ultimately powered the Apollo missions and put American astronauts on the moon. This achievement not only marked a significant milestone in human history but also represented a major victory for the United States in the Space Race against the Soviet Union.

Beyond space exploration, Paperclip scientists made substantial contributions to aviation technology. Their work advanced supersonic flight research, jet propulsion, and aircraft design. These advancements not only bolstered America’s military capabilities but also had significant impacts on civilian aviation, contributing to safer and more efficient air travel.

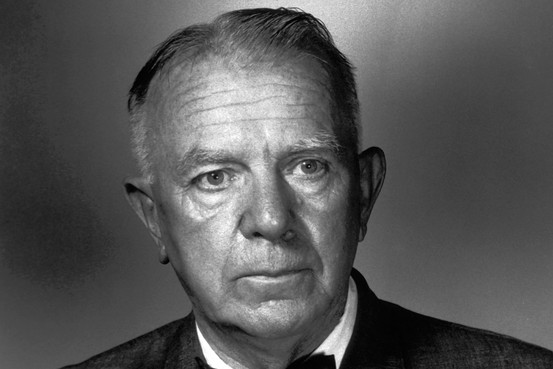

In the fields of medicine and biology, Paperclip recruits brought valuable knowledge that advanced several fields. Hubertus Strughold, despite later controversy over his wartime activities, made significant contributions to space medicine. His work on the effects of extreme environments on the human body was crucial for ensuring astronaut safety during space missions. Other scientists contributed to advancements in areas such as high-altitude physiology and the treatment of hypothermia.

The fields of electronics and computing also benefited from the influx of German expertise. Scientists and engineers recruited through Paperclip contributed to the development of advanced radar systems, guidance systems for missiles, and early computer technology. These advancements had wide-ranging applications, from enhancing national defense capabilities to laying the groundwork for the digital revolution.

Chemical and materials science saw significant progress as well. German scientists brought with them advanced knowledge in areas such as synthetic rubber production, new plastics and polymers, and chemical processes that would find applications in various industries. This expertise helped fuel the post-war economic boom and technological innovation in the United States.

In the fields of military technology, beyond rocketry, Paperclip scientists contributed to advancements in areas such as submarine technology, chemical weapons research (although the development of such weapons was officially prohibited), and various other defense-related fields. While ethically problematic, this knowledge played a role in shaping U.S. military strategy and capabilities during the Cold War.

The influx of European scientists helped reshape the American scientific landscape, influencing research methodologies, academic practices, and the overall direction of scientific inquiry in the United States. Many Paperclip scientists took up positions in universities, passing on their knowledge to new generations of American scientists and engineers.

Furthermore, the program had a significant economic impact. The expertise brought by these scientists led to numerous patents and innovations, estimated to be worth billions of dollars. These advancements not only strengthened America’s technological edge but also contributed to its economic dominance in the post-war years.

It’s important to note, however, that while these contributions were significant, they came at a moral cost. The ethical compromises made in recruiting scientists with Nazi pasts raised questions about the price of progress and the long-term implications of prioritizing scientific advancement over moral considerations.

Legacy and Ongoing Debate

The legacy of Operation Paperclip remains contentious, sparking ongoing debates about the ethical implications of prioritizing scientific advancement over moral considerations. While the program undoubtedly accelerated American scientific progress in key areas, it also raised profound questions about the moral costs of such advancements and the long-term consequences of compromising ethical standards in the name of national security.

The program’s long-term effects include:

- Ethical debates in scientific communities about the use of unethically obtained data

- Increased scrutiny of government secrecy and the limits of national security justifications

- Ongoing historical reassessment of the immediate post-war period and the early Cold War years

On the positive side, Operation Paperclip contributed significantly to America’s technological edge during the Cold War. The influx of German expertise played a crucial role in advancing fields such as rocketry, aviation, and space exploration.

The total value of contributions made by Paperclip scientists has been estimated at over $10 billion in patents and industrial processes. Many Paperclip recruits went on to receive prestigious awards and played key roles in major industries and technological sectors. Their influence extended beyond immediate technological gains, helping to reshape the American scientific landscape and influencing research methodologies and academic practices.

However, these advancements came at a significant moral cost. The program effectively allowed many former Nazis, some of whom were implicated in war crimes, to escape justice and build new lives in the United States. This not only contradicted America’s stated commitment to denazification but also denied closure and accountability to victims of Nazi atrocities. The willingness to overlook or actively conceal the Nazi pasts of recruited scientists raised serious questions about the ethical boundaries the U.S. government was willing to cross in pursuit of scientific knowledge and military advantage.

The case of Hubertus Strughold, known as the “father of space medicine,” illustrates the ongoing nature of this ethical debate. Despite his contributions to the U.S. space program, Strughold’s connection to human experimentation during World War II led to the retirement of an award named in his honor as recently as 2013, decades after his recruitment through Project Paperclip.

Furthermore, the program set a troubling precedent for prioritizing perceived strategic advantages over ethical considerations and international law. This approach arguably influenced subsequent U.S. policies and actions during the Cold War and beyond, contributing to a mindset where the ends were often seen as justifying the means in matters of national security.

Conclusion

The story of Operation Paperclip challenges us to consider the long-term consequences of short-term strategic decisions and the price of progress when it comes at the expense of moral clarity. As science and technology continue to advance at a rapid pace, the ethical questions raised by this Cold War-era program remain relevant, urging us to carefully consider the moral implications of our pursuit of knowledge and power.