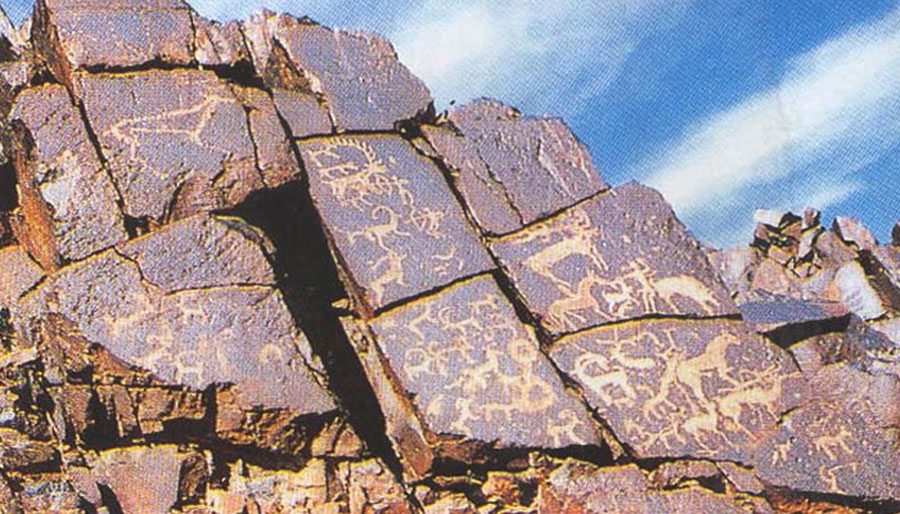

The Petroglyphic Complexes of the Mongolian Altai, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2011, comprise three significant rock art sites located in the high mountain valleys of northwestern Mongolia. These sites – Tsagaan Salaa-Baga, Upper Tsagaan Gol, and Aral Tolgoi – contain large concentrations of petroglyphs and funerary monuments that document the development of human culture in the region over approximately 12,000 years.

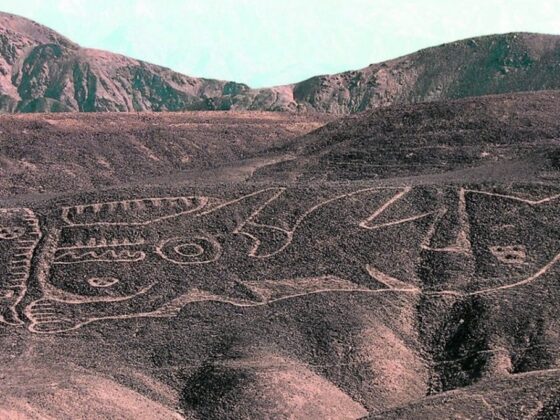

Dating back as far as 11,000 BCE, the petroglyphs provide an exceptional record of prehistoric and early historic communities in the northwestern Altai Mountains, at the intersection of Central and North Asia. The earliest images were created when parts of the land were heavily forested and ideal for large wild game. These depict animals such as mammoths, rhinoceros, elk, and ostriches, reflecting the inhabitants’ dependence on hunting.

As the Altai landscape transformed into its present mountain steppe character, later images began to show the emergence of animal herding as a dominant economic way of life. The most recent petroglyphs illustrate the transition to horse-dependent nomadism, a defining characteristic of the Eurasian steppe zone.

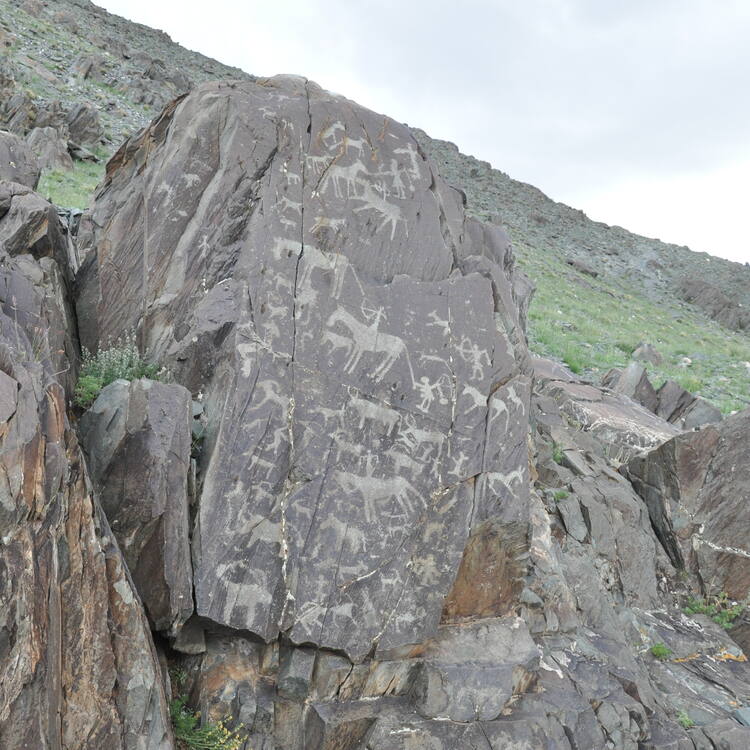

The petroglyphs across the three sites are considered the largest of their kind in terms of area, quantity, scientific value, historical significance, and artistic merit. They feature a wide range of subjects, including:

- Deer: Commonly depicted and holding significant cultural importance.

- Leopards: Often shown mid-leap with long, twisted tails, believed to symbolize energy.

- Wild pigs: Their depictions mark the transition from the Eneolithic to the Bronze Age.

- Horsemen: Reflecting the shift to a nomadic, horse-based culture.

In addition to the rock art, the sites also contain other archaeological features such as burial mounds, tombs, stone statues, and sacrificial sites. These structures range in date from the Upper Paleolithic to the late Middle Ages, each with its own cultural and religious significance.

The petroglyphs have remained largely pristine due to their relative inaccessibility, protected by both terrain and weather. They have been minimally affected by human or animal activity, serving as an enduring testament to pre- and early historic life in the region.

Research conducted at one of these complexes, the Biluut Petroglyph Complex, has provided further insights into the chronology and distribution of the rock art. A team led by Richard Kortum has documented approximately 12,000 individual figures and non-figurative marks. Their analysis shows that 73.5% of the identifiable figures are from the Bronze Age, 23.3% from the Iron Age, 1.4% from the Turkic period (550-750 AD), and 1.8% from the pre-Bronze Age or “Archaic” period.

The petroglyphs are not randomly distributed across the landscape. Different periods and types of figures show preferences for specific locations within the complex. For example, Archaic petroglyph-makers favored the Khuiten Gol Delta area, while Bronze Age artists preferred other locations such as Broken Mountain and Spring House Bluffs.

Some of the most impressive petroglyphs are the Turkic figures on the western slope of one of the hills, measuring up to 2.4 meters from nose to tail. These may be among the largest petroglyphs in Mongolia, if not all of Central Asia.

The Petroglyphic Complexes of the Mongolian Altai offer a unique window into the lives, beliefs, and environmental changes experienced by the inhabitants of this region over millennia.